Kongō class battlecruiser

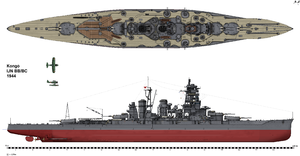

Line drawing of Kongō in her 1944 configuration |

|

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators: | |

| Succeeded by: | Amagi class battlecruiser |

| Built: | 1911–1915 |

| In commission: | 1913–1945 |

| Planned: | 4 |

| Completed: | 4 |

| Lost: | 4 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Battlecruiser (later Battleship) |

| Displacement: | 1915: 27,500 long tons (27,941 t) standard 1932: 36,600 long tons (37,187 t) standard[1] |

| Length: | 1915: 704 ft (215 m) 1932: 728 ft (222 m)[1] |

| Beam: | 101 ft (31 m)[1] |

| Draught: | 31.9 ft (9.7 m) |

| Propulsion: | 4 shafts; Parsons turbines; 8/11 boilers; 136,600 shp (101,900 kW) |

| Speed: | As completed: 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h) After refit: 30.5 knots (56.5 km/h)[1] |

| Range: | 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km) at 14 knots (26 km/h) |

| Complement: | 1437 |

| Armament: |

8 × 14-inch (356 mm) /45 calibre guns[1] |

| Armour: | deck: 2.3–1.5 in (57–41 mm)(later strengthened +101mm on ammo storage, +76mm on engine room) turrets: 9 in (227 mm) barbettes: 10 in (254 mm) belt: 8–11 in (203–279 mm) |

| Aircraft carried: | 3 |

The Kongō class battlecruisers (金剛型巡洋戦艦 Kongō-gata junyōsenkan) were a class of ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) constructed immediately before World War I. Designed by British naval architect George Thurston, the lead ship of the class was the last Japanese capital ship constructed outside of Japan. Displacing 27,500 long tons (27,941 t) upon completion, the vessels of this class were considered the first fully modern capital ships of the IJN.[2] Four vessels of the class (Kongō, Hiei, Kirishima, and Haruna) were completed from 1913 to 1915: Kongō in a Vickers shipyard in Britain, the latter three in Japanese shipyards.

Following World War I and the signing of the Washington Naval Treaty, Hiei was placed in reserve and reconfigured as a training vessel and a transport to avoid being scrapped, while Kongō, Kirishima and Haruna were placed in reserve in their original configuration. During the 1920s, all but Hiei were reconstructed and reclassified as battleships. Following Japan's withdrawal from the London Naval Treaty, all four were reactivated and underwent a massive second reconstruction. Following the completion of these modifications, which increased top speeds to over 30 knots (35 mph), all four were reclassified as fast battleships.

The Kongō class battleships were the most active capital ships of the Japanese Navy during World War II, participating in most major engagements of the war. Hiei and Kirishima acted as escorts during the attack on Pearl Harbor, while Kongō and Haruna supported the invasion of Singapore. All four participated in the battles of Midway and Guadalcanal. Hiei and Kirishima were both lost during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942, while Haruna and Kongō jointly bombarded Henderson Field. The two remaining battleships spent most of 1943 shuttling between Japanese naval bases before participating in the major naval campaigns of 1944. Haruna and Kongō engaged American surface vessels during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Kongō was sunk by submarine attack in November 1944, while Haruna was sunk at her moorings by air attack in Kure Naval Base in late July 1945.

Contents |

Design

The design of the Kongō class battlecruisers came about as a result of the Imperial Japanese Navy's modernization programs, as well as the perceived need to compete with the British Royal Navy.[3]

In March 1908, the Royal Navy launched HMS Invincible (1907) at Newcastle upon Tyne. Armed with eight 12-inch (30 cm) main guns, Invincible rendered all current—and designed—Japanese capital ships obsolete by comparison.[1] In 1911, the Japanese Diet passed the Emergency Naval Expansion Bill, authorizing the construction of one battleship (Fusō) and four armoured cruisers, to be designed by British naval architect George Thurston.[3][4] In his design of the class, Thurston relied on many techniques that would eventually be used by the British on the Tiger-class.[1]

Under the terms of the contract signed with Vickers in November 1910, one member of the Kongō class—the lead ship Kongō—was to be built in Britain. The design of the ships was from Vickers Design 472C (corresponding to the Japanese design designation B-46). Though early versions of the design featured eight or ten 12-inch guns, sixteen 6-inch (152 mm) guns, and eight 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes, the armament was upped to eight 14-inch (360 mm)/45 calibre guns.[5]

The final design of the battlecruisers was an improved version of the Lion-class, displacing an estimated 27,940 tonnes (27,500 long tons).[6] It also called for eight 14-inch guns mounted in four twin gun turrets (two forward and two aft) with a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph).[2]

Ships

Four vessels of the Kongō class were completed from 1911 to 1915. The first, Kongō, was constructed by Vickers-Armstrong in a British shipyard, while the remaining three—Hiei, Haruna and Kirishima—were constructed in Yokosuka (Yokosuka Naval Yard), Nagasaki (Mitsubishi Heavy Industries), and Kôbe (Kawasaki Shipbuilding Corporation), respectively.[4][6] Due to a lack of available slipways, the latter two were the first Japanese warships to be built by private shipyards.[4] Completed by 1915, they were considered the first modern battlecruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy.[1] According to naval historian Robert Jackson, they "outclassed all other contemporary [capital] ships".[6] The design was so successful that the construction of the fourth battlecruiser of the Lion-class—HMS Tiger—was halted so that design features of the Kongō class could be added.[6]

Kongō

Kongō was laid down 17 January 1911 at Barrow-in-Furness, launched 18 May 1912, and commissioned 16 August 1913. She arrived in Yokosuka via Singapore in November 1913 to undergo armaments sighting checks in Kure Naval Arsenal, being placed in reserve upon her arrival.[3] On 23 August 1914, Japan formally declared war on the German Empire as part of her contribution to the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, and Kongō was deployed near Midway Island to patrol the communications lines of the Pacific Ocean, attached to the Third Battleship Division of the First Fleet.[3] Following the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, Kongō and her contemporaries (including the ships in the Nagato-class, Ise-class and Fuso-class classes) were the only Japanese capital ships to avoid the scrapyard.[7] On 1 November 1924, Kongō docked at Yokosuka for modifications which improved fire control and main-gun elevation, and increased her antiaircraft armament.[3] In September 1929, she began her first major reconstruction. Her horizontal armour, boilers, and machinery space were all improved, and she was equipped to carry Type 90 Model 0 floatplanes.[3][N 1] When her reconstruction was completed in 31 March 1931, she was reclassified as a battleship. From October 1933 to November 1934, Kongō was the flagship of the Japanese Combined Fleet, before being placed in reserve when the flag was transferred to Yamashiro.[3]

On 1 June 1935, Kongō's second reconstruction began.[3][8][N 2] Japan's withdrawal from the London Naval Treaty[10] led to reconstruction of her forward tower to fit the Pagoda-Style of design, improvements to the boilers and turbines, and reconfiguration of the aircraft catapults aft of Turret 3. Her new top speed of 30 knots (35 mph; 56 km/h) qualified her as a fast battleship.[3] The modifications were completed on 8 January 1937.[3][8] In either August[11] or November 1941,[8] she was assigned to the Third Battleship Division with her three sister ships, and sailed on 29 November as part of the main body—four fast battleships, three heavy cruisers, eight destroyers—for the Japanese invasion of Malaya and Singapore.[8][11] Following the destruction of the British Force Z, the Main Body departed for French Indochina, before escorting a fast carrier task force in February during the invasion of the Dutch East Indies.[3] Kongō provided cover for Japanese carriers during attacks on the Dutch East Indies in February and Ceylon in March and April.[3][8] Kongō and Hiei were part of the Second Fleet Main Body during the Battle of Midway, but were diverted north on 9 June to assist in the invasion of the Aleutian Islands.[3][12] Kongō and her sisters engaged American naval forces in the Battle of Guadalcanal. During this engagement Kongō and Haruna bombarded Henderson Field with 430 14-inch and 33 6-inch shells on 13 October 1942.[12][13] Following armament and armour upgrades in late 1943 and early 1944,[3] Kongō sailed as part of Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa's Mobile Fleet during the Battle of the Philippine Sea.[14] During the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Kongō sortied as part of Admiral Kurita's Center Force, scoring hits on an American escort carrier and sinking or damaging two destroyers during the Battle off Samar.[3][15] Kongō and an escort, Urakaze, were sunk northwest of Taiwan on 21 November 1944 by the submarine USS Sealion II, after being hit on the port bow by two or three torpedoes.[9][15][16][17] Approximately 1,200 of her crew—including her Captain and the commander of the Third Battleship Division, Vice Admiral Yoshio Suzuki—were lost.[16] She was removed from the Navy List on 20 January 1945.[3]

Hiei

Hiei was laid down at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal on 4 November 1911, launched 21 November 1912, and commissioned at Sasebo 4 August 1914, attached to the Third Battleship Division of the First Fleet.[9][18] After conducting patrols off China and in the East China Sea during World War I, Hiei was placed in reserve in 1920.[18] After undergoing minor reconstructions in 1924 and 1927, Hiei was demilitarized in 1929 to avoid being scrapped under the terms of the Washington Treaty; she was converted to a training ship in Kure from 1929 to 1932.[9][15][18] All of her armour and most of her armament were removed under the restrictions of the treaty and carefully preserved.[18] In 1933, she was refitted as an Imperial Service Ship and—following further reconstruction in 1934—became the Emperor's ship in late 1935.[18][19] In 1937, following Japan's withdrawal from the London Treaty, Hiei underwent a massive reconstruction along lines similar to those of her sister ships.[N 3] When the reconstruction was completed on 31 January 1940, Hiei was reclassified as a battleship.[15][18] Hiei sailed in November 1941 as an escort of Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's carrier force which attacked Pearl Harbor.[9][18] Hiei provided escort cover during carrier raids on Darwin in February 1942, before a joint engagement with Kirishima that sank an American destroyer in March.[15][18][20] She participated in carrier actions against Ceylon and Midway Island, and was subsequently drydocked in July.[18][21] Following carrier escort duty during the Battles of the Eastern Solomons and Santa-Cruz, Hiei departed as the flagship of Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe's Combat Division 11 to bombard Henderson Field on the night of 12–13 November 1942.[22][23] When the fleet encountered Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan's Task Group in Ironbottom Sound, the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal ensued.[24] In an extremely confusing melee, Hiei disabled two American heavy cruisers—killing two rear admirals in the process—but was hit by about 85 shells from the guns of cruisers and destroyers, rendering her virtually unmaneuverable.[18][23] Abe transferred his flag to Kirishima, and the battleship was taken under tow by the same ship, but one of her rudders froze in the full starboard position.[24] Over the next day, Hiei was attacked by American aircraft many different times.[18][23] While trying to evade an attack at 14:00, Hiei lost her emergency rudder and began to show a list to stern and starboard.[18] Hiei was scuttled northwest of Savo Island on the evening of 13 November by Japanese destroyers.[23][24]

Kirishima

Kirishima's keel was laid in Mitsubishi's Nagasaki yard on 17 March 1912. She was launched about a year and a half later (1 December 1913) and transferred to Sasebo Naval Arsenal for fitting out. After her completion on 19 April 1915, she served off Japan, China and Korea's coasts during the First World War. After the war, she alternated between being based in Japan and patrolling off Japanese ports. On 14 September 1922, she collided with a destroyer (Fuji), causing minor damage to both ships.[25] Kirishima also assisted rescue efforts in the aftermath of the devastating 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, which destroyed most of Tokyo. After being sent to the reserve fleet in December 1923, she received a refit during 1924. Returning to the main fleet, the battlecruiser operated off China for periods of time in 1925–1926, until she returned to reserve from 1927 to 1931 in preparation for a major reconstruction.[N 4] Her superstructure was rebuilt, and she received extensive upgrades to armour, propulsion, and waterline bulges. After a period of fleet duty in the early 1930s, she underwent a two-year reconstruction (1934–1936) to rebuild her as a Fast Battleship.[25] This upgrade improved her engine plant, redesigned the superstructure, lengthened the stern, and enabled her to equip floatplanes. After serving as a transport and support-ship during the Second Sino-Japanese War, Kirishima escorted the aircraft carrier strikeforce bound for the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Following the start of World War II, Kirishima served as an escort during carrier attacks on Port Darwin and the Dutch East Indies.[2] Kirishima joined her sister ships in escorting naval sorties against Ceylon.[26] She once again served escort duty during the disastrous Battle of Midway, before transferring to Truk Lagoon in preparation for operations against American landings on Guadalcanal. After participating in the Battles of the Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz, Kirishima joined Hiei in a night attack on 13 November 1942. Following the loss of the latter on the evening of the 13th, Kirishima subsequently engaged American battleships on the night of the 14th/15th. Although she managed to inflict significant damage on USS South Dakota (BB-57), she was in turn crippled by USS Washington (BB-56).[24] With her engines largely disabled and listing heavily to starboard, Kirishima was abandoned in the early morning of 15 November 1942. She capsized and sank at 03:25 with the loss of 212 of her crew.[25]

Haruna

Haruna was laid down at Kobe by Kawasaki on 16 March 1912, launched 14 December 1913, and formally commissioned 19 April 1915.[27] After a short patrolling duty off Sasebo, Haruna suffered a breech explosion during gunnery drills on 12 September 1920; seven crewmen were killed and the No. 1 turret badly damaged.[27] After a long period of time in reserve, Haruna underwent her first modernization from 1926 to 1928. The process upgraded her propulsion capabilities, enabled her to carry and launch floatplanes, increasing her armour capacity by over 4,000 tons,[2] and was shortly thereafter reclassified as a Battleship.[27] She was overhauled a second time from 1933 to 1935, which additionally strengthened her armour and reclassified her as a fast battleship. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Haruna primarily served as a large-scale troop transport for Japanese troops to the Chinese mainland.[27] On the eve of the commencement of World War II, Haruna sailed as part of Vice-Admiral Nobutake Kondō's Southern Force. On 8 December 1941, Haruna provided heavy support for the invasion of Malaya and Singapore.[28] She participated in the major Japanese offensives in the southern and southwestern Pacific in early 1942, before sailing as part of the carrier-strike force during the Battle of Midway.[27] Haruna bombarded American positions at Henderson Field at Guadalcanal, and provided escort to carriers during the Solomon Islands campaign. In 1943, she deployed as part of a larger force on multiple occasions to counter the threat of American carrier strikes, but did not actively participate in a single battle.[27] In 1944, Haruna was an escort during the Battle of the Philippine Sea and fought American surface vessels off Samar during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.[29] She was the only one of the four battleships in her class to survive 1944.[30] Haruna remained at Kure throughout 1945, where she was sunk by aircraft of Task Force 38 on 28 July 1945, after taking nine bomb hits at her moorings.[31] She was subsequently raised and broken up for scrap in 1946.[27]

Specifications

Armament

Main battery

The primary armament of the Kongō class was eight 14-inch (360 mm)/45 calibre naval guns.[1] Each gun was 648.4 inches (16.47 m) in length,[32] and weighed 86 metric tons (85 long tons).[33] The shells fired by the main guns varied throughout the lifespan of the class. During World War I, Armour-Piercing Type 3 shells were used, each of which weighed 1,400 pounds (640 kg). In 1925, APC Type 5 shells replaced the previous ammunition, with APC No.6/Type 88 shells replacing these in 1928.[33] During World War II, APC Type 91 shells were used. Each of these shells weighed 1,485 pounds (674 kg), and was fired at an initial muzzle velocity of 2,543 feet per second (2,790 km/h).[32] With an approximate firing rate of two shells per minute and a firing range of 38,770 yards (35.45 km),[32] each 14-inch gun had a barrel-life of 250–280 rounds. Ammunition stowage for the Kongō class was around ninety shells per gun.[33] In 1941, dyes were introduced to the IJN. Kongō's shells used red dye, Hiei's black, and Kirishima's blue, while Haruna did not use shell-dyes.[33]

The main guns of the Kongō class were mounted in four double turrets (two forward, two aft), each of which weighed 654 metric tons (644 long tons).[33] Originally, the turrets possessed an elevation capability of -5/+25 degrees, a significant improvement on British designs of the time, which were limited to a maximum +15/+20 degree elevation.[33] By the start of World War II, the various reconstructions of the vessels had increased the elevation range of the main turrets to -5/+43 degrees.[32] With an arc of -150/+150 degrees, the Kongō class also benefited from having all four of its turrets either forward or aft, whereas their British counterparts often relied on heavily restricted midships turrets.[2] The turrets of the class were generally considered superior to their British counterparts, with the 1946 United States Naval Technical Mission to Japan Report 0-47(N)-1 stating that "[the Japanese 14-inch turrets] are similar to the British 15-inch turrets, but some improvements have been made...[including] better flash-tightness and working chambers."[33] In 1920, the #1 Turret of Haruna suffered a breech explosion which destroyed the starboard gun, killing seven men and destroying the armoured roof of the turret.[27]

Secondary armament

The secondary battery of the Kongō class varied significantly throughout their careers. Originally, the secondary armament was configured as sixteen 6-inch (152 mm)/50 calibre Vickers Mark M guns mounted in single casemates.[1] Each gun could fire a 100-pound (45 kg) shell a distance of 22,970 yards (21.00 km), at a firing rate of between four and six shells per minute.[34] During their reconstructions in the 1930s, two of these guns were removed from each ship, bringing the final configuration to fourteen 152 mm guns. During the later portions of their careers, the Kongō class was fitted with a varying number of 5-inch (127 mm)/40 calibre Type 89 Dual Purpose guns.[2] These guns could be employed as either an anti-surface and anti-aircraft (AA) capacity, and were the standard heavy AA guns of the Imperial Japanese Navy.[35] Each gun could fire a 50.7-pound (23.0 kg) shell at a speed of 2,379 feet per second (2,610 km/h).[35] The 5-inch turrets, employing a two-gun configuration, were relatively easy to construct and were thus used with greater frequency as the war continued.[36] The guns also possessed "excellent elevation and training speeds", yet were often hindered by their slow muzzle velocity and comparatively low firing ceiling.[36] These four ships relied on 25 mm (0.98 in) Type 96 AA guns,[1] the standard light AA guns used by the Japanese Navy during World War II, and carried up to 118 of them in varying configurations of single-, double- and triple-mounts.[1]

Armour

The Kongō class battlecruisers were designed with the intention of maximizing speed and maneuverability, and as such were not as heavily armoured as later Japanese capital ships.[1] Nevertheless, the Kongō class possessed significant quantities of armour, and were heavily upgraded during their modernizations. In their initial configuration, the Kongō class possessed an upper belt that was 6 inches (152 mm) thick, and a lower belt with a thickness of 8 inches (203 mm).[37] Vickers Cemented was used in the construction of the Kongō, while the original armour of the other three was constructed of a variation of Krupp Cemented Armour, designed by the German Krupp Arms Works.[37] Subsequent developments of Japanese armour technology relied upon a hybrid design of the two variations until drastic changes were made during the design of the Yamato class in 1938. The armoured belt near the bow and stern of the vessels was strengthened with an additional 3 inches (76 mm) of cemented armour.[37] The conning tower of the Kongō class was very heavily armoured, with variations of Krupp Cemented Armour up to 14 inches (360 mm) thick.[37] The turrets were lightly armoured compared to later designs, with a maximum plate thickness of 9 inches (229 mm).[1] The deck armour ranged from 1.5 to 2.75 inches (38 to 70 mm).[1]

During the reconstructions that each ship underwent during the interwar period, most of the armour of the Kongō class was heavily upgraded. The main lower belt was strengthened to be a uniform thickness of 8 inches, while diagonal bulkheads of a depth ranging from 5 to 8 inches (127 to 203 mm) reinforced the main armoured belt.[38] The upper belt remained unchanged, but was closed by 9-inch bulkheads at the bow and stern of the ships.[38] The turret armour was strengthened to 10 inches (254 mm), while 4 inches (102 mm) were added to portions of the deck armour.[38] The upgrades increased the armour displacement by close to 4,000 tons on each ship, violating the terms of the Washington Treaty.[2] Even after these modifications, the armour capacity of the Kongō class remained much less than that of newer capital ships, a factor which played a major role in the sinking of Hiei and Kirishima at the hands of U.S. Navy cruisers and battleships in 1942.[39]

Propulsion

As the Kongō class was created with the purpose of building high-speed battlecruisers, their machinery produced a remarkably higher power than most other contemporary battleships, whose design and construction focused on armour or firepower at the expense of speed. On trials, these plants were able to produce between 78,275 to 82,000 shaft horsepower (58,370 to 61,000 kW), driving the ships through the water at 27.54 knots (51.00 km/h; 31.69 mph) to 27.78 knots (51.45 km/h; 31.97 mph). The power was generated by 36 Yarrow boilers, all of which consumed coal; to increase performance, the coal was sprayed with oil. The boilers themselves were located in eight separate rooms. Kongō, Hiei and Kirishima were given Parsons turbines; Haruna received Brown–Curtis turbines.[40] During their reconstructions into fast battleships, the Yarrow boilers were removed and replaced with eleven oil-fired Kampon boilers.[27] These upgraded boilers gave the Kongō and her sisterships much greater power, with the class capable of speeds exceeding 30.5 knots (56.5 km/h; 35.1 mph). This made them the only Japanese battleships fully suited to operations alongside fast carriers.[2]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Sources disagree on the reconstruction's beginning and ending dates. Whitley gives 20 October 1928 to 20 September 1931,[8] but Kongo's Combined Fleet Tabular Record of Movement gives dates of September 1929 to 31 March 1931,[3] and Breyer agrees with a range of September 1929 to March 1931.[9]

- ↑ As with the first, sources disagree as to the exact dates of the second reconstruction. While Whitley and Combined Fleet agree on a starting date of 1 June 1935, Breyer uses January 1936; all sources agree that it ended in January 1937, but Breyer uses a more general "January 1937", rather than the exact date given by Whitley and Combined Fleet.

- ↑ Sources all disagree on the exact date. Whitley says 26 November 1936, Breyer says November 1936, and Combined Fleet gives 1 April 1937.[9][15][18]

- ↑ Sources disagree on the exact dates. While Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships says March 1927 to 31 March 1930, Kirishima's Combined Fleet Tabular Record of Movement states that it was from May 1927 to 16 April 1930.[4][25]

Citations

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 "Combined Fleet - Kongo class". Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, & Allyn Nevitt. http://combinedfleet.com/ships/kongo. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Jackson (2008), p. 27

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 Hackett, Robert; Kingsepp, Sander (6 June 2006). "IJN KONGO: Tabular Record of Movement". Combined Fleet. CombinedFleet.com. http://combinedfleet.com/kongo.htm. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Gardiner and Gray (1980), p. 234

- ↑ Gardiner and Gray (1980), pp. 223 and 234

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Jackson (2000), p. 48

- ↑ Jackson (2000), p. 69

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Whitley (1998), 182

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Breyer (1973), p. 333

- ↑ Willmott, p. 35

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Willmott, p. 56

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Whitley (1998), p. 183

- ↑ Swanston, p. 220

- ↑ Willmott, p. 141

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Whitley (1998), p. 184

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Wheeler, p. 183

- ↑ Tully, Anthony P. (July 2001). "The Loss of Battleship KONGO". Mysteries/Untold Sagas of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Combined Fleet. http://www.combinedfleet.com/eclipkong.html. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ↑ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 18.12 Hackett, Robert; Kingsepp, Sander (6 June 2006). "IJN HIEI: Tabular Record of Movement". Combined Fleet. CombinedFleet.com. http://combinedfleet.com/hiei2.htm. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ↑ Imperial Service Ships were used by Japanese royalty for naval transport

- ↑ Breyer (1973), pp. 333–334

- ↑ Breyer (1973), p. 334

- ↑ Swanston, p. 222

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Whitley (1998), p. 185

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Jackson (2000), p. 121

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Hackett, Robert; Kingsepp, Sander (2001–2009). "IJN KIRISHIMA: Tabular Record of Movement". Combined Fleet. CombinedFleet.com. http://combinedfleet.com/Kirishima.htm. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ↑ Boyle, p. 370

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 27.7 27.8 "Combined Fleet - tabular history of Haruna". Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, & Allyn Nevitt. http://combinedfleet.com/haruna.htm. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ↑ Willmott (2002), p. 56

- ↑ Boyle, p. 508

- ↑ Jackson (2000), p. 127

- ↑ Jackson (2000), p. 129

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 "Combined Fleet - 14"/45 gun". Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, & Allyn Nevitt. http://combinedfleet.com/360_45.htm. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ↑ "Combined Fleet - 6"/50 gun". Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, & Allyn Nevitt. http://combinedfleet.com/155_50.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Combined Fleet - 5"/40 gun". Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, & Allyn Nevitt. http://combinedfleet.com/127_40.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Moore, p. 165

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 McCurtie, p. 185

- ↑ Stille, p. 14

- ↑ Whitley (1998), pp. 178, 180

References

- Boyle, David (1998). World War II in Photographs. London. Rebo Productions. ISBN 1-84053-089-8

- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and battle cruisers, 1905–1970. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. OCLC 702840.

- Cawthorne, Nigel (2005) Victory in World War II. Arcturus Publishing. ISBN 1-84193-351-1

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870219073.

- Jackson, Robert (editor) (2008). 101 Great Warships. London. Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-905704-72-9

- Jackson, Robert (2000). The World's Great Battleships. Brown Books. ISBN 1-89788-460-5

- Keegan, John (1989). The Second World War. Penguin Books. ISBN 0143035738

- Kennedy, David M. (Editor) (2007). The Library of Congress World War II Companion. New York. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5219-5

- McCurtie, Francis (1989) [1945]. Jane's Fighting Ships of World War II. London: Bracken Books. ISBN 1-85170-194-X

- Moore, John (1990) [1919]. Jane's Fighting Ships of World War I. London: Studio Editions. ISBN 1-85170-378-0

- Schom, Alan (2004). The Eagle and the Rising Sun; The Japanese-American War, 1941-1943. Norton & Company. ISBN 2-00201-594-1

- Steinberg, Rafael (1980) Return to the Philippines. Time-Life Books Inc. ISBN 0-80942-516-5

- Swanston, Alexander & Swanston, Malcom (2007). The Historical Atlas of World War II. London: Cartographica Press Ltd. ISBN 0-7858-2200-3

- Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 155750184X.

- Willmott, H.P. & Keegan, John [1999] (2002). The Second World War in the Far East. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 2004049199.

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||